By Bill Miller and Emily Drooby

‘Brought Home to Where He Belongs’

GREENWOOD HEIGHTS — Raymond Smith, a Catholic kid from Brooklyn, was missing in action in the so-called “forgotten war” with North Korea in the early 1950s, but his sister never forgot him.

His repatriated remains finally came home Sept. 21. A graveside ceremony with military honors was held four days later at Green-Wood Cemetery. Late summer greenery decked the historic grounds beneath a deep-blue dome of sunlit sky. Then, a 21-gun salute pierced the serenity, followed by the mournful bugle call of Taps.

A U.S. Army color guard performs military honors at the graveside services for Pvt. Raymond Smith, of Brooklyn. The soldier, who died in the Korean War, was missing in action since 1950. Here, his sister, Helen Bilbao (seated, in white shirt) and her daughter, Linda Kiers (to Helen’s right) absorb the patriotism during the ceremony at Green-Wood Cemetery. (Photo: Bill Miller)

Members of a U.S. Army color guard performed the honors for their fellow soldier. Raymond was 18 when he met his fate in desperate combat with masses of Chinese troops in the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, early in December 1950.

His older sister, Helen Bilbao of Brooklyn, now 93, attended the arrival of his casket at JFK Airport and the graveside services. Helen’s daughter, Linda Kiers, son, Gary Bilbao, and their families, accompanied her. Also, veterans who didn’t know Raymond paid their respects at the service and the wake, held earlier, at Clavin Funeral Home.

While amazed and grateful for the attention, Helen asked her son to tell reporters the family’s story. He recounted how his grandparents separated and his mother and uncle wound up in foster care.

“They really didn’t have a core family,” Gary Bilbao said. “But they had each other. They were the family.”

Eager to Go

Bilbao said his mother is five years older than “Uncle Raymond,” whom he never met. But she told him how nuns in the Diocese of Brooklyn cared for the siblings and how the children also lived in foster homes. They attended St. Michael’s Parish on 42nd Street in Sunset Park.

“She used to hold his hand and take him to school,” Bilbao said. “Either together or separately, they went to different homes until my mother was old enough to get a job.”

Bilbao said his mother married in her early 20s, but she and Raymond remained close.

Raymond Smith of Brooklyn enlisted in the U.S. Army at age 18, but became missing in action during the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, December 1950. (Photo: Courtesy of Raymond Smith’s family)

“She would put him up every once in a while,” he said. “She had a basement apartment with my father, and my uncle used to knock on the window. She’d give him money so he could jump on a bus to the YMCA and play basketball.”

His mother’s only portrait of her brother was a tiny black-and-white print taken in a photo booth on Coney Island. But it grew fuzzy over time, so Bilbao, a photographer, scanned it and touched it up on his computer.

The image shows Raymond — a typical teen in post-World War II Brooklyn — wearing a white t-shirt under a dark cardigan. He has neatly parted hair, expressive eyes, and an easy smile.

“To me, he looks like a happy kid,” Bilbao said. “My mother said he was a happy kid. He seemed like he had his act together.”

Hollywood produced many combat movies during and after World War II, and Raymond saw plenty of them. That made sense to his sister because he always played Army as a little kid, Bilbao said.

He noted that the family only recently learned a side note about Raymond from military officials.

“One of their tidbits of information was that, when he was 14 years old, he joined the Navy,” Bilbao said with a chuckle.

Naval officers subsequently learned he misrepresented his age and gave him an honorable discharge.

“Nobody knew,” Bilbao said. “But he was sort of a down-and-out kid. I guess if you don’t have a real family life, the military is a good option.”

When Raymond turned 18, he was free to enter military service. He picked the Army.

“He was eager to go,” his nephew said. “And from what I could gather, it was about six months in the Army, and they shipped him off to North Korea, never to be seen again.”

MacArthur’s Resolve

There is no record of how Private Raymond A. Smith died while fighting the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army in North Korea.

But descriptions of what he faced at the Chosin Reservoir are well documented in the battle record of his unit — Company A, 1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division.

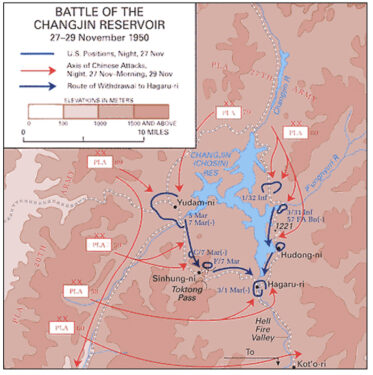

This map shows the defense positions of U.S. forces (in blue) at the Battle of Chosin (Changjin) Reservoir. The red lines show the attack routes of Chinese troops. The position of Raymond’s Smith’s Company A was with the 32nd Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division (dark blue curved line, right side of the reservoir). (Photo: U.S. Army via Wikimedia Commons)

The 7th ID was part of the U.S. response to North Korea’s invasion of South Korea on June 25, 1950. Other countries in the fledgling United Nations also participated. Commanding all of them was World War II hero General Douglas MacArthur.

In mid-September, the 7th ID and the 1st Marine Division made the risky but successful amphibious landings at Inchon. Weeks later, North Korean forces pulled back across their border, but MacArthur resolved to crush them. So he sent Marines and the 7th ID in pursuit.

Raymond’s 32nd Regiment merged with others, including South Korean units, into the 31st Regimental Combat Team.

The RCT moved north along the east side of the Chosin Reservoir, while the Marines set up along the west side.

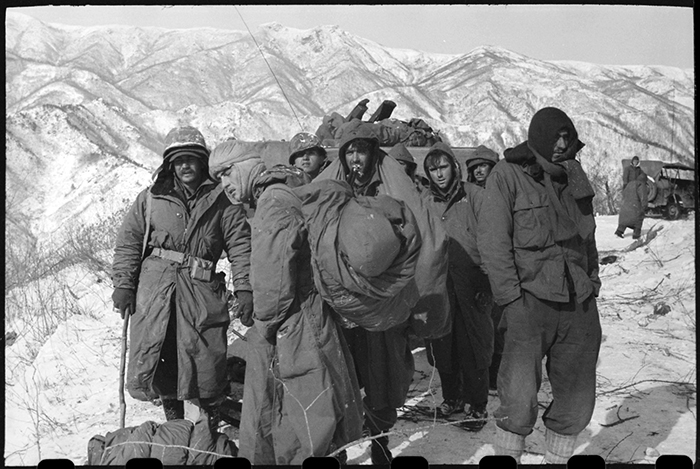

Bone-chilling cold shivered Raymond and fellow infantrymen after sundown on Nov. 27. Then the People’s Volunteer Army (PVA) unleashed hell on all sides of the frozen lake.

The Battle of Chosin Reservoir had begun.

Mao Zedong’s Rage

The People’s Republic of China entered the conflict after its leader, Mao Zedong, warned the UN against deploying troops near the Yalu River, his country’s border with North Korea.

In early November, with MacArthur undeterred, the enraged Mao ordered the total destruction of UN forces. The PVA snuck into North Korea by night and hid beneath dense forest cover during daylight.

Unbeknownst to MacArthur’s intelligence officers, the Chinese already controlled the rugged terrain overlooking the Chosin Reservoir when Raymond’s unit arrived.

Also, MacArthur didn’t know that the Chinese force numbered about 120,000 troops. The 31st RCT had about 2,500.

The attacks on Raymond’s Company A are described in the book “East of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950” by Lt. Col. Roy E. Appleman, U.S. Army (retired). On these pages, Maj. Wesley Curtis reported:

“During the hours of darkness, the enemy exploited his terror weapons such as bugles, whistles, flares, burp-guns, and infiltration tactics. Fighting became very close, and in some instances, hand-to-hand.

“Occasionally, a Chinese soldier would infiltrate inside the perimeter and run about like a madman, spraying his burp-gun until he was killed. By dawn on Dec.1, members of the Task Force had been under attack for 80 hours in sub-zero weather. None had slept much. None had washed or shaved: none had eaten more than a bare minimum … Everyone seemed to be wounded … frozen feet and hands were common.”

The RCT’s commander was Lt. Col. Don Faith, a 32-year old veteran of World War II. Faith entered that war as a first lieutenant with the 82nd Airborne Division. By war’s end, he wore the silver oak cluster insignia of lieutenant colonel.

Five years later, he had the grim task of preventing a massacre of his men at the Chosin Reservoir, including an estimated 600 wounded.

The Fate of Task Force Faith

Remnants of the 31st RCT loaded onto trucks and tried to head south, but the PVA throttled the advance with blown bridges and hastily assembled roadblocks. At each stall, the enemy unloaded sniper fire, mortar rounds, and heavy machine-gun fire.

Lt. Col. Faith led an assault on a roadblock but was mortally wounded in the chest with grenade fragments. His men put him in a truck, but it sustained heavy gunfire and rolled off the road out of their reach.

Lt. Col. Don Faith, commander of Raymond Smith’s unit in Korea, was a veteran of World War II, having made combat jumps with the 82nd Airborne Division in Sicily and Normandy, France (D-Day). He was at Operation Market-Garden in Holland and the Battle of the Bulge in Belgium. His story is recounted in several books and the documentary “Task Force Faith: The Story of the 31st Regimental Combat Team.” (Photo: U.S. Department of Defense via Wikimedia Commons)

About 1,500 frostbitten troops, depleted of ammunition, managed to straggle in disorganized groups away from the destruction, but Raymond was not with them. Nor was he among the prisoners released later by the PVA.

An estimated 1,000 men, including Raymond and Lt. Col. Faith, would remain missing in action for more than six decades.

For his heroism, Faith posthumously received the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest distinction for valor. The 31st RCT subsequently became known as “Task Force Faith.” His family finally received his remains in 2012.

Six years later, President Donald Trump had a summit with North Korean Leader Kim Jong-un. The U.S. then received 55 boxes of remains believed to be American troops killed during the Korean War.

Subsequently, those remains arrived at the Defense Department’s POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) lab at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii. Thus began a painstaking process involving DNA analysis.

“The military did an excellent job,” Bilbao said. “They matched that up with DNA that my mother had sent in. Sure enough, there was a match.”

For My Mom, It’s Closure

The DPAA confirmed on March 25 that Raymond had been identified. His remains arrived Sept. 21 at JFK Airport.

A full U.S. Army color guard carried his casket from the plane to a waiting hearse.

At the same time, a couple of dozen airport police officers, joined by firefighters and airline ground crews, stood nearby at attention. The officers saluted.

Helen and her family approached the casket. She gently placed her hand, wrapped in a rosary, on the flag-draped casket.

At the Sept. 25 graveside service, Helen received the tri-folded American flag and Raymond’s service awards: the Korean Service Medal, the Combat Infantry Badge, and the Purple Heart.

“The patriotism was overwhelming,” Bilbao said, “especially at the airport, with the American flag on the casket, and also the police all lined up and saluting. My mom really loved it; she’s very patriotic.

“And she’s amazed at how many people are interested, as my sister and I are.”

Deacon Chris Wagner of St. Bernard Parish, Bergen Beach, led the graveside prayers. “Honored” is how he described the experience.

“This gentleman is a patriot,” the deacon said. “The freedoms that we all share and enjoy are because of gentlemen and ladies like him. But he was from Brooklyn, just 18 years old, and had no clue where he was going. He perished there, lost in another country.

“But now we rejoice because he’s found, and he’s brought home to where he belongs.”

And for that, his sister has peace, Bilbao said.

“For him to be brought back to her, to be connected to him, is very important for her,” he said. “For my mom, it’s closure.”

These frostbite casualties of the embattled 1st Marine Division and the Army’s 7th Infantry Division managed to break out of the trap set by the People’s Volunteer Army of China at the Chosin Reservoir, North Korea, in December 1950. (Photo: National Archives and Records Administration via Wikimedia Commons)